The Untapped Power on Your Plate: A Deep Dive into Cuenca's Organic Food Revolution and the Surprising Key to Expat Health

To the uninitiated, the stories sound almost mythical. Expats, drawn to the colonial charm and temperate climate of Cuenca, Ecuador, arrive with the usual collection of life's aches, pains, and health concerns that accumulate over time. They brace for the initial challenge of the city's 8,400-foot altitude, expecting shortness of breath, a touch of brain fog, and a period of general fatigue. And for many, that adjustment period comes as predicted. But then, something remarkable begins to happen.

After a few months of navigating the cobblestone streets, the initial struggles give way to a wave of unexpected and profound well-being. It’s a transformation whispered about in cafes and shared in online forums, a phenomenon that often catches even the healthiest newcomers by surprise. People who have battled with their weight for years attest to shedding 20, 30, even 40 pounds without a punishing diet, simply by living and eating in their new home. Chronic skin conditions clear up, revealing a healthier glow. Troublesome, long-standing issues with sleep, persistent headaches, and a general lack of vitality begin to fade, sometimes disappearing entirely. Eyesight seems to sharpen, the persistent mental fog that many accept as a part of modern life lifts, and a newfound stamina emerges, turning a short walk into a pleasant stroll and then into an invigorating hike.

This journey to better health isn't always a straight line. It has its peaks and valleys, moments of feeling fantastic followed by days of feeling just okay. But the consistent report is that each new peak of well-being is higher than the last, eventually settling onto a new, elevated plateau of health that many thought was a thing of their past.

What is this "Cuenca effect"? Is it the cleaner mountain air? The famously pure water? The simple act of walking more in a city built for pedestrians? It is, most likely, a symphony of all these factors. But the conductor of this orchestra, the single most powerful and transformative element, is undoubtedly the food. The everyday ingredients that find their way onto the plates of Cuencanos and the expats who live among them hold a power that is often underestimated. This isn't just about sustenance; it's about a fundamental change in the building blocks of health. However, the story is far more complex than a simple tale of "everything is natural here." To truly understand this health revolution, one must look beyond the surface and delve into the rich, fertile, and often challenging soil of Ecuador's agricultural landscape. It's a story of myth and reality, of silent struggles and incredible opportunities—a story that reveals how your dinner plate is directly connected to the future of this nation.

The Myth of the Pristine Paradise: Deconstructing the Ecuadorian Plate

For many North Americans, the first foray into a Cuencano mercado is a sensory revelation. The vibrant colors of the fruits and vegetables, the sheer variety of potatoes, the unfamiliar yet enticing aromas—it all points to a food culture that feels more connected to the earth. And in many ways, it is. There is a kernel of truth to the idea that the baseline quality of food is higher here. Even the most commercially produced, lowest-common-denominator produce in Ecuador can be a step up from its equivalent in the United States.

The reasons are multifaceted. The industrial food complex in Ecuador, while it exists, is not as pervasive or chemically intensive as in more developed nations. There's generally less industrial waste contaminating the soil and water. The sheer variety and overwhelming availability of processed, packaged, and "crap food" that lines every aisle of a Western supermarket is less pronounced. While you can certainly find cookies, chips, and sugary drinks, they don't dominate the landscape in the same way. This environment naturally nudges people, expats and locals alike, toward whole, unprocessed foods.

This reality has given birth to a pervasive and comforting myth: that all food in Ecuador, particularly the food found in the local markets, is inherently organic. Many expats operate under the assumption that the gnarled carrots and soil-dusted potatoes sold by a woman in a traditional shawl must be free from the chemical intervention that plagues the perfectly uniform produce back home. They believe that only the large, sterile supermarkets, with their plastic-wrapped offerings, are the domain of pesticides and fertilizers.

This is a dangerous misconception.

The truth is that the use of chemical fertilizers and pesticides is widespread throughout Ecuador. It is not the heavy-handed, systematic application seen in the vast monocultures of North American agribusiness, but it is a common and accepted practice. For the average small-scale farmer, the choice is a brutally simple one. Losing a crop to pests or poor soil is a direct threat to their family's survival. The investment in a fully organic, sustainable farming system—which requires immense knowledge, constant vigilance, and often, more labor—is a luxury they simply cannot afford. It is far safer and more economically rational to use a bit of chemical fertilizer to ensure a harvest, or a dose of pesticide to save it from ruin, than to risk everything on an ideal.

This is especially true for the larger-scale commercial farms that supply the nation's restaurants, exporters, and a significant portion of the supermarket chains. When dealing with high-demand crops like tomatoes, onions, and potatoes, the primary driver is consistent, predictable output. These are commercial operations, and they use commercial tools to get the job done. While the chemical load may not reach the levels that cause immediate, acute health crises, the chemicals are still present. They are absorbed by the plants and, in turn, by the people who eat them.

So, while the average expat experiences a health boost simply by switching from a standard American diet to a standard Ecuadorian one, this is more a testament to the poor quality of the former than the absolute purity of the latter. The improvement is real, but it represents a move from "very bad" to "less bad." For those who have made health a top priority—and for many expats, it is the top priority—this is a crucial distinction. The journey to optimal health doesn't end with the standard Ecuadorian plate; it begins there. The next level of well-being, the faster, more consistent, and more dramatic improvements, can only be unlocked by seeking out the food that is truly, intentionally, and verifiably organic. And to find that, you must first understand the silent struggle of the people who produce it.

The Silent Struggle: Inside the Economics of Ecuador's Small-Scale Organic Farmer

The organic farming sector in Ecuador presents a fascinating paradox. On paper, it is a story of impressive growth. The nation boasts over 75,000 certified organic hectares, with more than 2,250 registered organic products, from primary crops to processed goods like chocolate and banana chips. Ecuador has become a significant player in the international organic market, exporting high-demand products like bananas and cacao to the United States and Europe. This growth, however, masks a much grimmer reality on the ground for the individual who is the supposed cornerstone of this movement: the small-scale farmer.

To understand their struggle, you must first understand the structure of Ecuadorian agriculture. It is a world of two extremes. On one side, you have "Agricultura Empresarial" – large, corporate-style farms. This group, representing just 15% of agricultural units, controls a staggering 80% of the farmland and 63% of the water used for irrigation. Their focus is on agro-export and large-scale commercial crops, and their methods are often chemically intensive.

On the other side is "Agricultura Familiar Campesina" (AFC) – the small family farms. They make up 84.5% of all farms but are squeezed onto just 20% of the land and have access to only 37% of the irrigation water. Despite these disadvantages, their contribution is immense. They produce over 64% of the total agricultural output for the nation and a remarkable 60% of the food that is actually consumed within Ecuador. They are the backbone of the country's food sovereignty.

Yet, this vital role does not translate into economic prosperity. The organic farmer, in particular, finds themselves in an almost impossible position. They are trying to compete in a market dominated by the low prices and high volume of the commercial giants. The official "organic" certification, while a point of pride, offers little tangible economic benefit in the local market. Supermarket chains might carry some organic options, but this doesn't guarantee the farmer a fair price, nor does it solve the fundamental problem of scale.

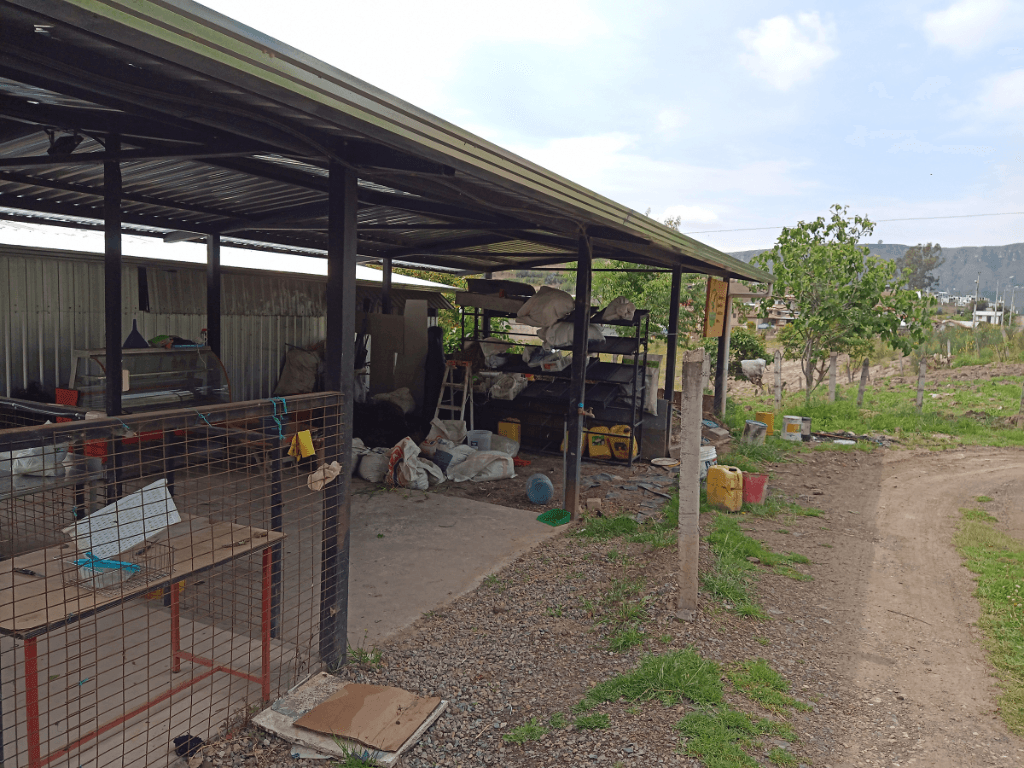

Let's paint a picture of a typical small-scale farmer, the kind you might meet at a weekly feria. They are not business people in the modern sense; they are people of the land. Their ambition is not to build an empire, but to sustain their family. They lack the training, the tools, and often the interest in becoming business-minded entrepreneurs. They don't keep detailed records of sales and production, they don't invest in marketing, and they don't have the capacity to build the complex logistical systems required to supply a larger market. Their entire operation is geared towards selling a small amount of produce every few days.

Consider the economics. Imagine a farmer who manages to bring 80 pounds of various vegetables to the market each week. If we are generous and assume they make a profit of $2 per pound (a highly optimistic figure, given that many items sell for less than $1 to the final consumer), their weekly profit from vegetables is $160. That's $640 a month. Perhaps they also sell some meat, like cuyes (guinea pigs), a high-value item. To earn another $200 in profit, assuming a $5 profit per animal, they would need to sell 40 cuyes a month. Anyone who frequents the local markets knows this is an absurd number for a small vendor. You are far more likely to see a seller with a dozen cuyes at most.

But let's stick with our optimistic fantasy. Our farmer is making a profit of $840 a month. In Ecuador, the basic minimum wage is around $450. So, they are earning less than two minimum wages. From this "profit," they must cover all their living expenses. Assuming they own their home, basic living costs for one person can easily reach $400 a month. This doesn't include any "luxuries" like new clothes, a television, or a smartphone. It is bare-bones survival.

This leaves them with $440 a month for "business investment." But we haven't even factored in their real business costs: the fee for their market stall, the cost of hiring a truck to transport their goods, and other incidental expenses. Let's say they dream of buying their own small van to have more control over their logistics. A used van might cost $8,000. At a savings rate of $440 a month, it would take them nearly two years to afford it—and that's based on our wildly optimistic profit calculations and assumes no personal emergencies or unexpected costs. The reality is that for most, it would take four years, five years, or a lifetime.

This is why there is a "missing middle" in Ecuadorian agriculture. You have the tiny producers selling a handful of cuyes, and you have the massive distributors who buy and sell them by the thousand. There is almost no one in between, no mid-sized, growing organic businesses. The economic ladder is missing its rungs.

Compounding this problem is a severe generational gap. The youth in rural communities see the back-breaking labor and the meager financial returns of their parents and grandparents, and they want no part of it. They see no future in farming. The few young people who do remain on the farm often do so out of love and loyalty to their family, helping out of a sense of duty, not with an entrepreneurial vision to grow the business. The knowledge, the passion, and the connection to the land are at risk of dying out with the current generation.

This is the silent struggle. While the demand for organic food grows, and the health of expats hangs in the balance, the very people who could supply this demand are trapped in a cycle of subsistence, unable to scale, unable to invest, and unable to build a future. It's a broken system. But within this brokenness lies a powerful and symbiotic opportunity.

The Bridge Builders: A New Vision for a Healthier Ecuador

The current situation presents a perfect storm of needs and resources, a puzzle waiting for the right pieces to be put together. On one side, you have a growing population of health-conscious expats. They have the desire for high-quality, nutrient-dense food and, crucially, the disposable income to pay a fair price for it. They are living proof of the life-changing benefits of a truly clean diet, and they represent a concentrated, motivated market.

On the other side, you have the small-scale organic farmers. They possess the skills, the land, and the product. They are the guardians of a healthier, more sustainable way of farming. What they lack is the bridge to the market. They are producers, not marketers, logisticians, or business developers.

This is where the "bridge builders" come in. The solution to this impasse lies not in trying to turn every farmer into a businessperson, but in creating a new role in the food chain: a professional, business-minded intermediary who can connect the two sides. These are not the exploitative middlemen of old, but rather partners in a new, more equitable system.

Imagine a team of people whose skills have almost nothing to do with planting seeds. Their expertise lies in organizing markets, managing supply chains, and implementing quality control. They build user-friendly websites for ordering, they create marketing campaigns to reach new customers, and they develop efficient delivery routes to ensure that produce arrives fresh from the farm to the consumer's doorstep. They handle the administrative tasks, the business development, the customer service, and the human resources that are essential for any modern business to grow.

By creating this infrastructure, they liberate the farmers to do what they do best: farm. The farmers are guaranteed a fair and consistent price for their products, reducing their economic risk and allowing them to invest in their land and techniques. They no longer have to worry about hiring a truck or spending their days at a market stall. They can focus on improving their crop quality and yield.

This model creates a virtuous cycle. The expats get reliable access to the fresh, high-quality organic food they need to thrive. The farmers get the financial stability and market access they need to build a sustainable business. And the "bridge builders" create a viable enterprise that generates employment and injects new energy and innovation into the agricultural sector. This is how you build the "missing middle." This is how you create a system where a farmer can grow from selling a dozen cuyes to selling a hundred, and then two hundred, creating a true family business that the next generation might actually want to be a part of.

This is not just a theoretical model. It is a solution that is beginning to take root.

A Solution in Action: The Shungo Foods Model

This vision of a connected, equitable, and efficient organic food system is the driving force behind Shungo Foods. We are striving to be the number one supplier of organic food in Cuenca by acting as that essential bridge. Their mission is to build a reliable, secure, and professional logistics system that connects the farmer, the warehouse, and the delivery person, ensuring that the quality and freshness of the product are protected at every step.

We are tackling the most difficult part of the equation: the "last mile." We work to find the sweet spot between when a customer places an order and how quickly they can receive a product that is genuinely fresh. We are building the systems to ensure that orders are fulfilled completely and accurately, with responsive customer service and a simple, intuitive online platform for browsing and ordering.

Setting up this infrastructure is incredibly complex and expensive. It is the work that no single farmer can do on their own. When this work isn't done, the money flows to the large-scale commercial producers, where quality control is often an afterthought. In that world, as long as a tomato isn't visibly squashed or moldy, it's considered acceptable. Little thought is given to how it was stored, whether it was exposed to extreme temperatures, or if it was handled with poor hygiene. There is no accountability.

By choosing a service like Shungo Foods, you are choosing a different path. You are choosing a system built on transparency, quality, and a genuine respect for both the producer and the consumer.

Your Plate, Your Power: An Investment in Health and Community

As you plan your new life in Cuenca, you will be enchanted by its beauty, its culture, and its people. But do not miss out on one of the most profound opportunities the city offers: the chance to fundamentally transform your health. This journey is not just possible; it is easily within your reach. By making a conscious choice to nourish your body with powerful, nutrient-dense food, you will see the results in your energy levels, your mental clarity, your quality of sleep, and your overall well-being.

But your choice goes far beyond your own health. Every dollar you spend on true organic food is a vote for a better future. It is an investment in a struggling market that is vital for the health of this community. The prices for these products are necessarily higher, not because of greed, but because you are paying the true cost of creating a new industry from the ground up. You are funding the innovation, the training, and the technology that farmers need. You are paying for the logistics, the marketing, and the administrative capacity that allows a small operation to become a thriving business.

You are helping to build a system that benefits everyone: the expats who gain a new lease on life, the local children who grow up with access to healthier food, and the elderly who can live their final years with vitality and dignity. You have an opportunity to be more than just a consumer; you can be a co-creator of a healthier, more equitable, and more sustainable Ecuador. It all starts with the simple, powerful choice of what you put on your plate.

Javier V.

10-year immigrant in Cuenca, Ecuador

Member of multiple local business circles and communities, including many English-speaking expat groups

Unlock More Essential Expat Insights

Don't navigate the exciting, yet often complex, world of expat life in Cuenca alone. Our newsletter is your direct line to even more powerful insights on the specific pain points we've discussed, offering practical solutions and strategies gleaned from years of on-the-ground experience.

Beyond advice, we'll also share trusted recommendations for service providers – from reliable facilitators and legal experts to property managers and community groups – who consistently go the extra mile to support expats like you. Think of it as your curated list of allies dedicated to your successful transition and long-term happiness in Ecuador.